Stone Age hunters, or so the story goes, discovered whitish, gelatinous lumps in the stomachs of young ruminants that had drunk their mother’s milk shortly before being caught. The milk had fermented into a kind of curd cheese in the stomach of the prey. This was presumably our ancestors’ first experience of ‘cheese’, and thousands of years ago the product was no doubt valued as a special delicacy.

Archaeological evidence from the Neolithic age indicates that cattle were already being bred in the area that is now the Swiss Confederation. So it is likely that people who used animal milk were also looking for a way to preserve this highly perishable but important foodstuff.

For centuries, the main product made from curdled milk was cottage cheese. The hard-cheese tradition was introduced to the Alpine regions by the Romans. The first mention of ‘Swiss’ cheese was made by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder in the first century: he described what he called “Caseus Helveticus”, the cheese of the Helvetians, who populated the territory of present-day Switzerland at that time. The first medieval source that mentions cheesemaking dates back to 1115 and comes from the Pays d’Enhaut in the former county of Gruyère. The Handfeste, or charter, of the city of Burgdorf from the year 1273 also refers to the cheesemaking in the Emmental valley.

Up until the early Middle Ages, the population of our region was almost entirely self-sufficient. The Alpine valleys were inhabited only where cereal crops could be grown. The Alps and their foothills had always been dominated by dairy farming. And wherever milk was produced, it had to be preserved, which meant turning it into butter, Ziger (whey cheese), quark and cheese. As the efficiency of the transport system improved, people were able to settle the more remote Alpine valleys. This resulted in the traditional ‘mush’ (mostly cabbage or crushed grains) being replaced by cheese as the staple food. It was known simply as d’Spys, which means ‘food’.

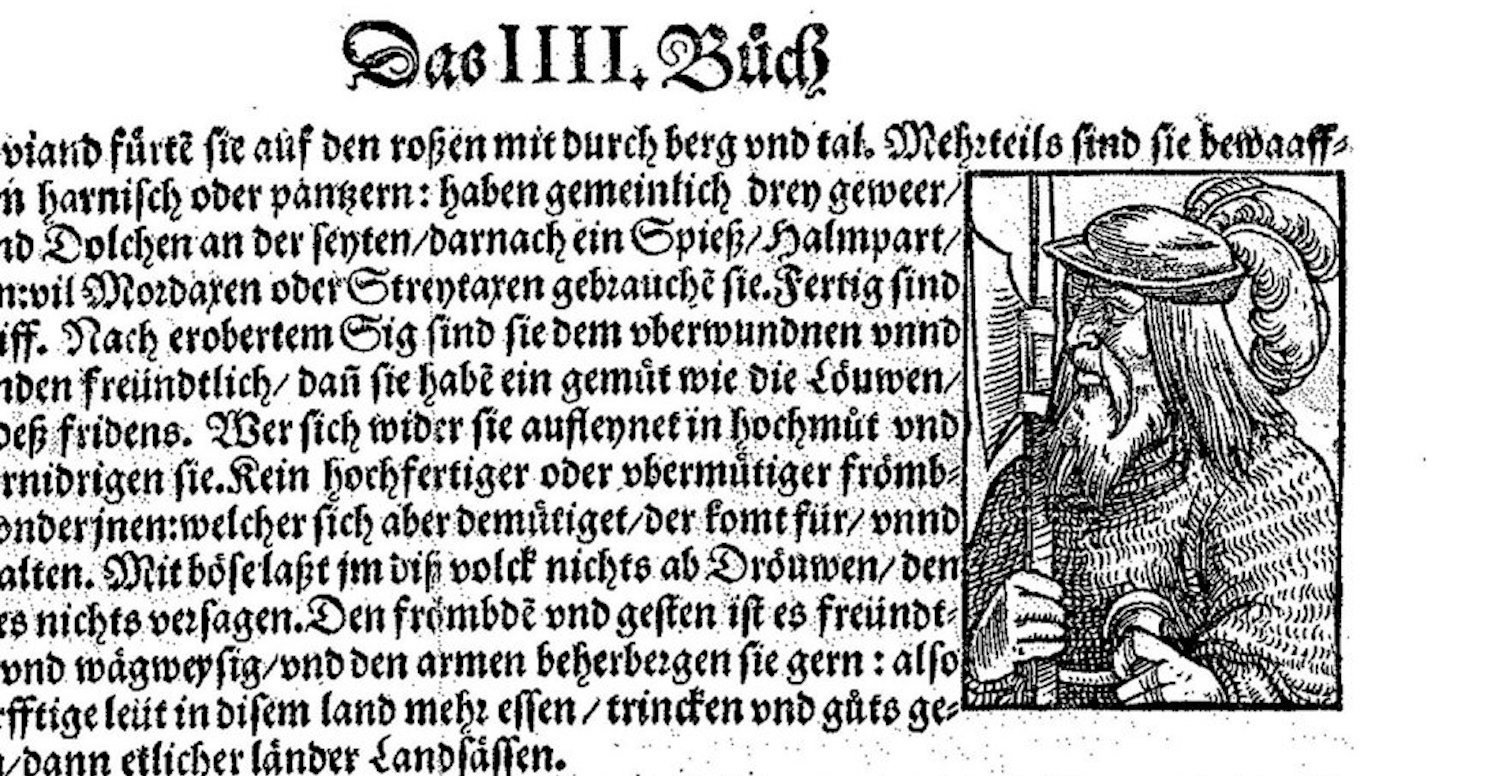

One of the first mentions of hard cheese. The picture shows the interior of a cheese dairy with a cheesemaker and butter-churner, from the “Stumpf Chronicle”, woodcut 1548 (Book 4, p. 291; this page from the 2nd edition, 1586).

In the early days of the Confederation, cheese was not only the principal food, but was also in widespread use as an alternative means of payment to money. It was customary to pay craftsmen and day-labourers, even the parish priest’s salary, “in cheese and money”. In fact, cheese was welcomed as a substitute for money even outside the Confederation. Thus alpine herdsmen used to carry their wheels of cheese over the Alpine passes to Italy and trade them for spices, wine, chestnuts and rice. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Alpine dairymen brought their surplus cheese down to the valley to sell. They were obliged by law to sell their goods on the markets themselves, since the authorities disapproved of intermediate trading. As the cheese trade grew, however, it became impossible to prohibit the activity of middlemen. The cheesemonger was a necessary link between the alpine herdsman and the consumer. They had what the alpine herdsman lacked: storage space and capital as well as marketing expertise and a customer network. As late as the 18th century, cheesemongers were still taking linen and fustian, coffee and tobacco to Alpine huts and farmhouses as payment for the wheels of cheese.

In those days, the same basic hard-cheese recipe was used throughout Switzerland. Local differences in the cheeses came about as a result of the different sizes of mountain pastures and varying methods of treatment during the ripening process. The more cows that spent the summer on the mountain pastures, the larger the cheese wheels that could be produced. But some of the basic methods of hard-cheese production that are still typical today were already emerging at that time:

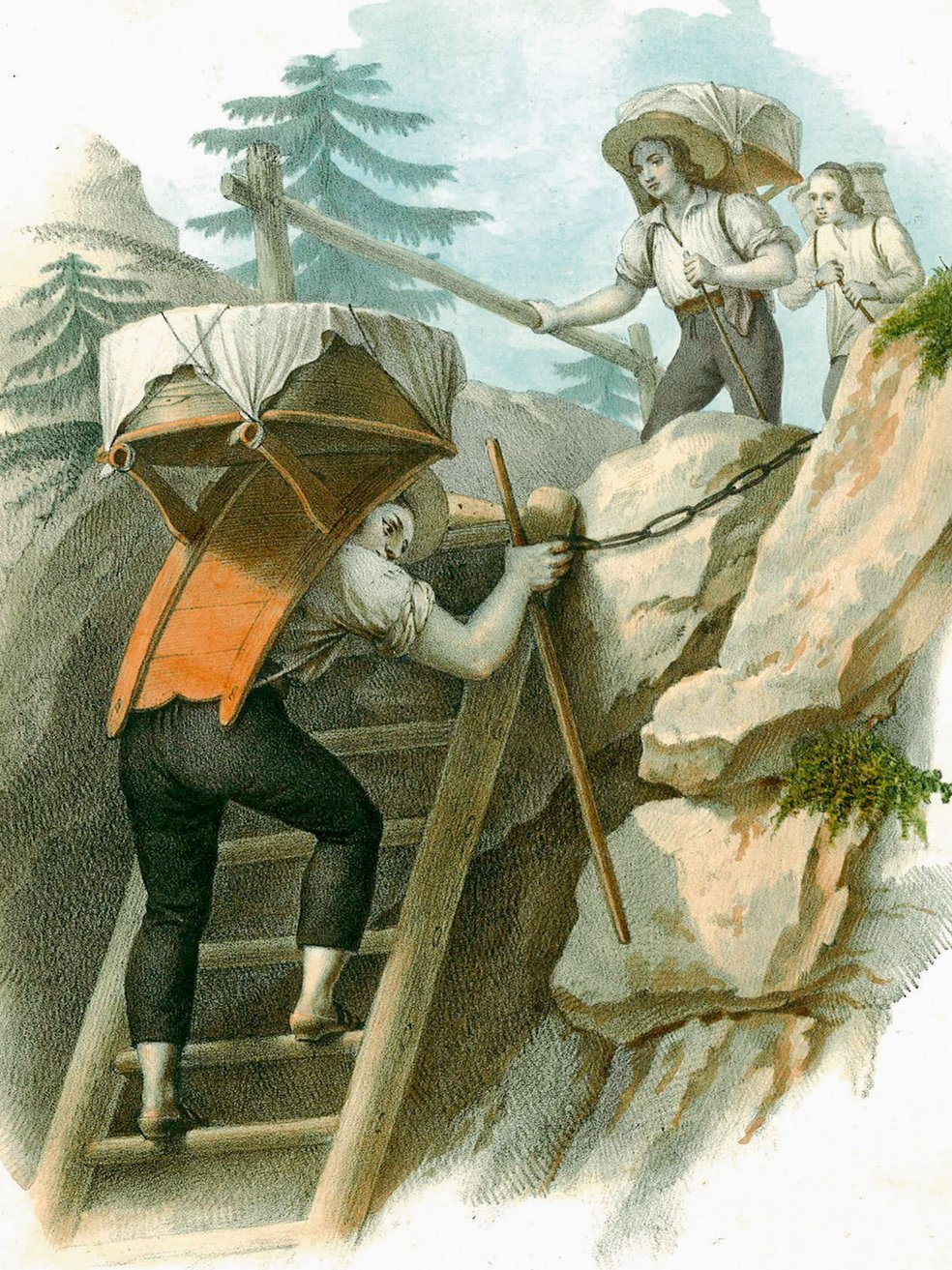

- “Sbrinz” and “Gruyère de rayon” (similar to today’s L’Etivaz AOP or Saanen-Hobelkäse) were left to dry and mature for over two years on their edge in well-aired racks, to make them less perishable and better for transport by pack animal.

- In the Gruyère region, people stuck to the original form of hard cheese and produced flat, washed-rind Gruyère.

- As late as the early 18th century, Emmental was hardly distinguishable from Gruyère. As a result, the French sometimes called it “Gruyère d’Emmental”, a confusing name that has survived here and there to the present day.

In the 18th century, consumer demand for hard cheese grew considerably on account of its longer shelf life. Even then it was true that the greater the demand, the higher the status of the producer. Soon cheesemaking was no longer limited to humble dairymen or herdsmen. In those days, however, people still believed that transportable cheese could only be produced in the Alps. But Philipp Emanuel von Fellenberg begged to differ and set up an experimental cheese dairy on his Hofwil estate in 1805.

Fellenberg soon proved that good cheese could also be produced in the lowlands. In 1815, Rudolf Emanuel von Effinger, the lord of Kiesen castle near Thun, built a cheese dairy there, the first Emmental village cheese dairy in the valley to be managed as a cooperative. The Swiss initially turned their noses up at the Emmental produced in the new valley dairies, but cheese production throughout Switzerland gradually shifted more and more to the valley and the Central Plateau.

From 1832 onwards in the Fribourg area, for example, ever more valley dairies sprang up. Within a very short time, the Alpine cheese dairies had lost their pre-eminence. Some alpine dairymen became cheesemakers in the numerous new village cheese dairies. Others bought up low-lying pastures and became resident mountain farmers. Still others moved abroad, above all to Eastern Europe and North America, where they built cheese dairies and produced mainly Emmental cheese. As a result, as early as the end of the 19th century it was no longer possible to protect the name “Emmental” for the cheese with large holes from Switzerland.

In 1834, the Canton of Berne alone exported 22,882 hundredweights of cheese. This was the start of “the great age of cheese”, during which many farmers and entrepreneurs were gripped by a real cheese fever – similar to the Californian gold rush.

Wild, reckless speculation led to fortunes being invested in the cheese trade. Although the enormous quantities of Swiss cheese being produced found a ready market at home and abroad, from 1875 onwards, marketing difficulties and price fluctuations began to make themselves felt, ruining countless farmers, cheesemakers and exporters.

In the ensuing slump, the industry came to its senses and realised that quality was of paramount importance. The farmers who supplied the milk needed in-depth knowledge of feeding and livestock stabling. The newly founded dairy schools gave cheesemakers the opportunity to improve the quality of their products. The traders also abandoned the malpractice of reserving the full-fat cheese for export and selling the low-fat cheese, in plentiful supply due to the growing demand for butter, on the home market. At that time, the Swiss population had every reason to complain that the more expensive and better cheese was going abroad. Today, Swiss cheese of the same excellent quality is available everywhere and enjoyed all over the world.

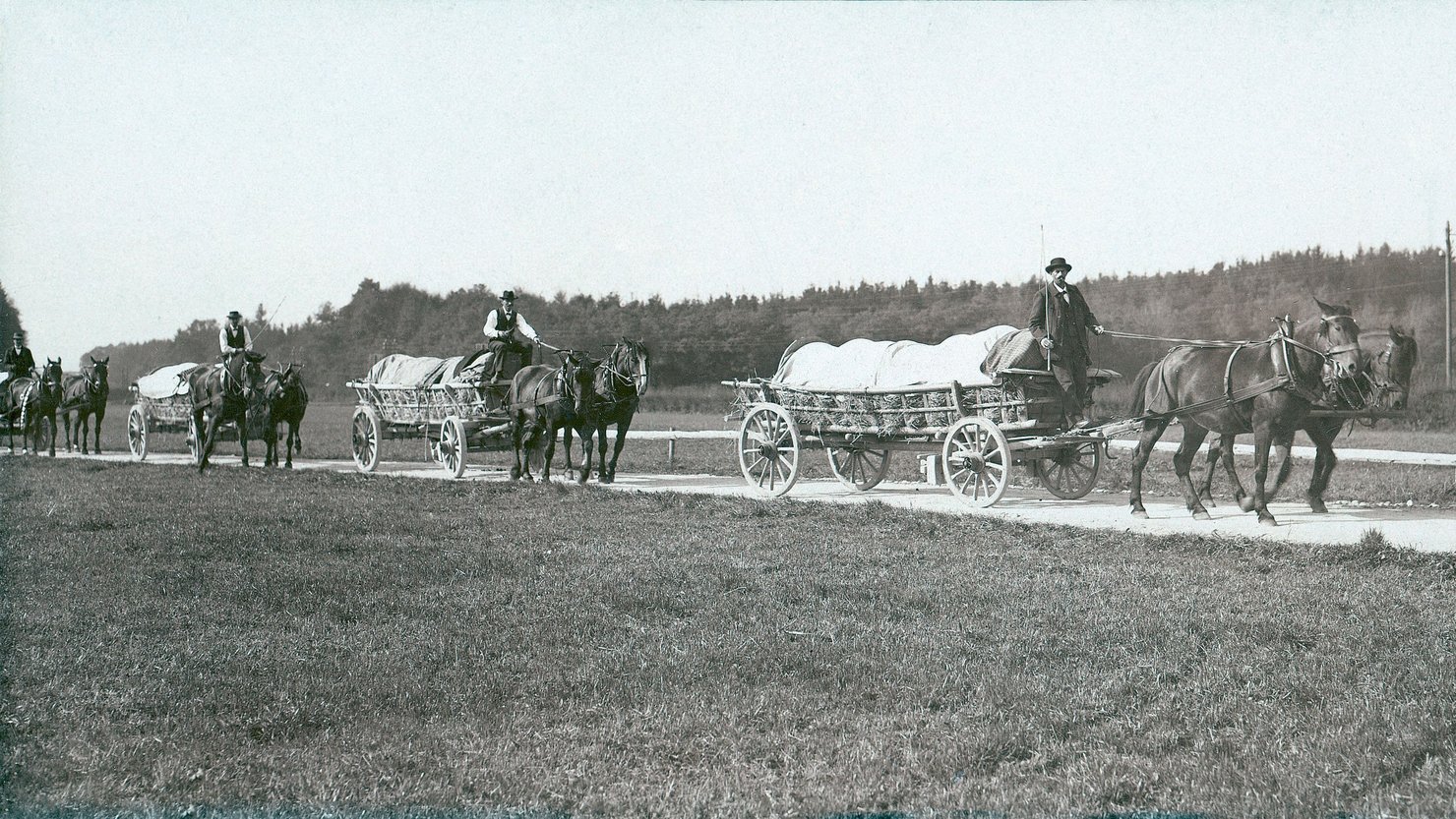

Four wagons and pairs belonging to Roth-Fehr & Co. carrying approx. 12 wheels of cheese each, on Lyssachstrasse; b/w photograph 1912 by Guido Roth (1882–1927)